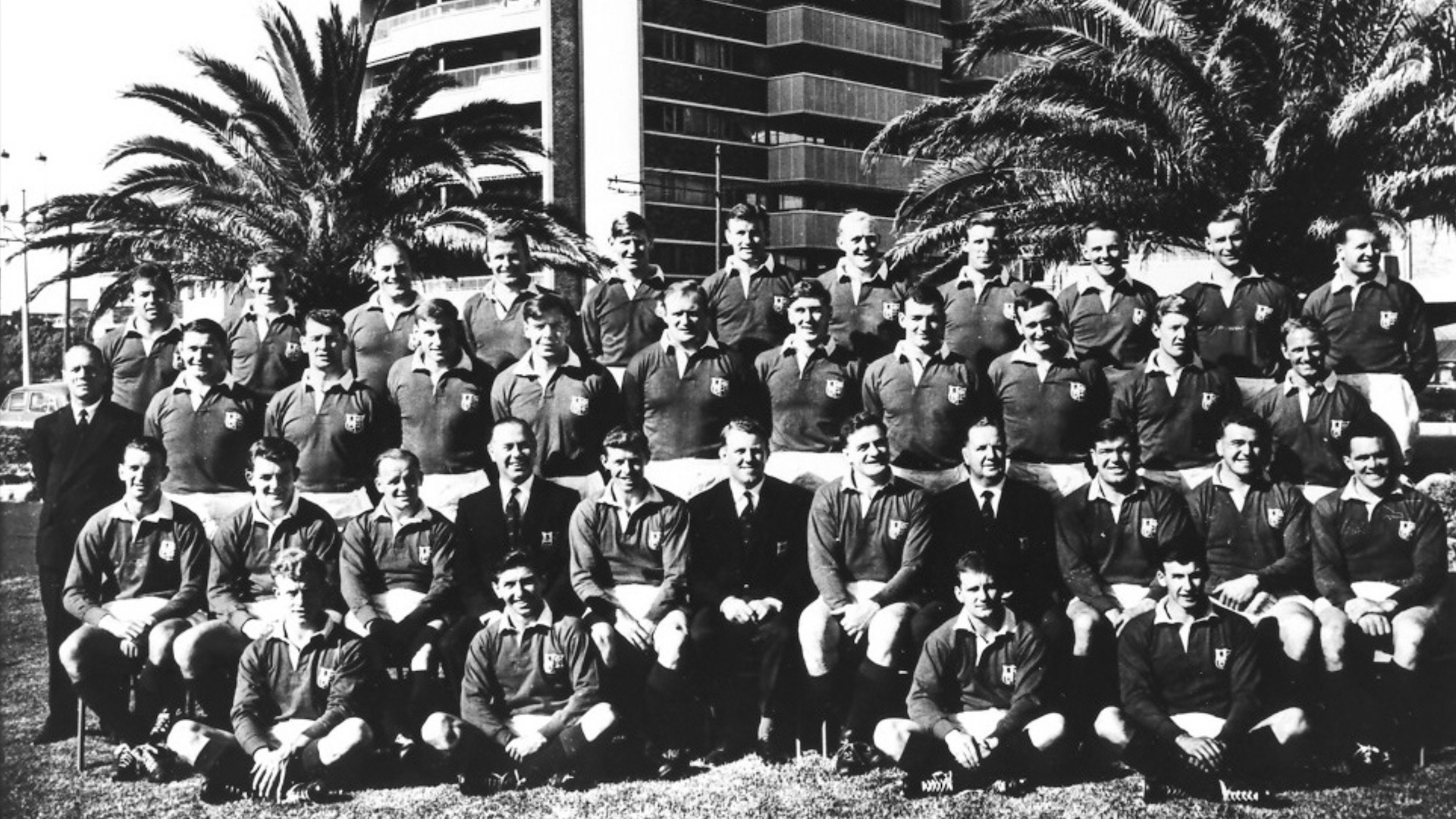

David Rollo is flicking through his scrapbook from the 1962 British & Irish Lions Tour of South Africa.

The memory may take a little longer to engage these days, but there is no mistaking the warm glow of recollection in the 86-year-old’s voice, nearly 60 years after the event.

“I thoroughly enjoyed my Tour,” says the former Scotland prop. “When you played for the Lions or you had your Lions blazer on, you felt on top of the world. Everyone respected who you were.”

Rollo, a full-time farmer during his rugby career, is relaying the squad’s eve-of-departure instructions before they headed off on a three-and-half-month odyssey from London on Friday 18 May, 1962.

For someone who “didn’t know much about the Lions at all, just a few bits I read in the newspaper”, the sense of anticipation must have been exquisite.

A pre-tour get-together in Eastbourne concluded with the party transported to the Washington Hotel in London’s swanky Mayfair, where relatives and friends were permitted to join them for tea at 4pm. Then it was off to South Africa House for a reception with the ambassador to London, back to the Washington for another reception with the Home Unions Tour Committee, “followed by dinner at 8pm in the Billington Room…”

And the day of departure?

“After lunch at 1pm, the coach will leave the Washington Hotel at 3.30pm to convey the party to London Airport North. It is essential the coach departs on time. Upon arrival at London Airport, the party will be conducted to a lounge where tea will be taken, and where they can be joined by any relative or friend wishing to take leave of them before departure. While refreshment is being served, it is anticipated custom and ticket formalities will be completed without need to examine individuals separately. The aircraft is due to take off at 6pm.”

A squad of 30 players – plus four replacements – played the first of 25 matches on 26 May in what was then Salisbury, in the former colony of Rhodesia, and is now Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe.

Their last game, on 28 August, was in Nairobi, Kenya, where they stopped off to play East Africa three days after a fourth and final Test against the Springboks in Bloemfontein.

‘Taking leave’ of loved ones was not the only consideration when players received a letter informing them of their selection.

Rollo was 27 at the time and ran the family farm in Fife with his elder brother. His daughter was only six months old. “I had to get permission to go from my wife and my brother,” he recalls. “Luckily all the spring crops were in by then and I was back in time for the harvest, so it wasn’t so bad.”

While Rollo had a living to return to, for others the Tour brought a marked change in circumstances.

Winger Ronnie Cowan, 80 later this year, is the youngest of the surviving Lions from the 1962 Tour. At 20 and six months, he was the youngest Scottish player ever to be picked for the tourists, a month younger than Craig Chalmers in 1989, and five months younger than Stuart Hogg in 2013.

“Financially the Tour was quite a disaster for me,” Cowan says. “I worked in the mill in Selkirk and they paid me off. They couldn’t afford for me to be away for three-and-a-half months, so seven or eight weeks before the Tour started, I found myself unemployed.

“The Scottish Rugby Union promised me they would get me something when I came back but of course that never happened.”

Indeed, Cowan never played for his country again. On his return from the Lions Tour, he followed the path trodden by his father Jimmy, and elder brother Stan, and went to rugby league, joining Leeds and forging a successful career in the 13-man code.

“It could have been the start of a long career playing for Scotland, but I was just a young lad,” he said. “Rugby league came along and offered me a career and off I went.”

Some suspected Cowan had already agreed professional terms before the Lions departed. Members of the squad were given 70 shillings a week (about £3.50) for expenses, but Rollo recounts that “Ron was the only player with spare pocket money to spend!” “Not that we needed much anyway,” he added. “Everything was laid on for us.”

The South African media dubbed Rollo ‘Tarzan’. He says he is unsure why, but his preternatural strength may have had something to do with it. At 5ft 11in and 14st 7lb, he would struggle to get a game on the wing in the current era of behemoths, yet he routinely dominated opposition props.

“At that time, I’d be standing on one leg and hooking the ball as a tighthead prop,” he said. “My forte was getting the ball against the head. I was strong enough to hold the opposition prop, even while I was standing on one leg, so the hooker could stand on both feet.

“I don’t know whether it had anything to do with my natural farm strength. I was always lugging 200lb-weight (around 90kg) bags of silage and fertilizer around, forking sheaths from the mill and manhandling cattle. You were building up your strength all the time.”

Rollo played for his club side, Howe of Fife, until he was 40, finishing his career as a number eight for the second XV. With a physique forged by farm work, he still maintained a daily fitness regime.

“I trained every night at 9.45pm, on the main road outside the farm gate,” he said. “I did eight lots of 200m, with the final two full sprints. If I could hold my breath, then I would go back in the house again. I was only out the house for 15 minutes, then back in for the 10 o’clock news. I did that seven nights a week, and never got fed up. It was the best training I did. I’ve still got a 33inch waist now!”.

My Lions Moment: Willie John McBride at 80

If his honed physique and habit of wearing his tartan kilt to official functions – the only Scot on Tour to do so – made him popular with the locals, Rollo’s tour was cruelly interrupted by injury.

He was poised for a place in the Test team alongside fellow prop and Lions legend Syd Millar – who played nine Tests across the Tours of 1959, 62 and 68, and went on to coach the 1974 Invincibles – before a rib issue intervened.

“I was first choice early on for the Saturday games with Syd but then I got injured and wasn’t available for the first two Tests,” he recalled. “We had no medical staff with us at all, and it wasn’t until I got home that I discovered I had a torn muscle around one of my ribs.

“It could have been X-rayed and we would have found out what it was. But I just had to wait until it got better. I did play later on (Rollo played 13 of the 25 matches overall) but wasn’t selected for the other Test matches. That was my big disappointment.”

If seeking out a local doctor was the only option for injured players, on other occasions it was handy having a player like Irish lock Bill Mulcahy – who had completed his medical training at University College Dublin and later became a doctor for Aer Lingus – in the party.

“I remember I’d been off for a couple of games and I came back and broke my nose,” recalls Cowan. “Bill Mulcahy put the bone in my nose back into position again and I carried on playing.”

The squad was accompanied by manager Brian Vaughan, a Royal Navy Commander who won eight England caps in the late 1940s and was then the president of the RFU. His assistant Harry McKibbin, a former Ireland centre who toured with the British Isles to South Africa in 1938, held the same position with the Irish RFU.

“Brian and Harry were more like teachers really,” Cowan recalls. “Neither were anything to do with coaching.

“(Captain) Arthur Smith was the de facto coach. He would tell us backs what to do, along with (fly-half) Gordon Waddell. It was probably Bill Mulcahy and Syd Millar with the forwards – just a group of lads doing the best they could, without being coached in any way.”

That lack of coaching certainly included lineouts, which to Cowan’s mind were “a complete farce”.

“As a winger, I was throwing the ball in,” he says. “It was a lottery, frankly. It was only (Scottish number eight) John Douglas and a few of the Welsh lads in the back row who were agile enough to be able to jump properly.

“The big lads – Mike Campbell-Lamerton, Keith Rowlands, Bill Mulcahy – were heavy men; they were not built for lineout jumping, so in those days a lineout was quickly followed by a scrum. You very rarely got the ball back. You threw it in, crossed your fingers and hoped for the best.”

Smith, a winger, was the first Scot to captain the Lions since 1927. Seven other compatriots have led a British Isles or Lions Tour party, from Bill Maclagan in 1891 through to Gavin Hastings in 1993.

Most were from the square-jawed, ‘follow me’ school of leadership. It is fair to say Smith, who was tragically taken by cancer aged just 42 in 1975, was a slightly different character.

An outstanding intellectual, Smith – who scored 12 tries in 33 Tests for Scotland from 1955 to 1962 and also toured with the 55 Lions – attended both Glasgow University and Cambridge University and had a PHD in mathematics.

“Arthur could talk about lots of subjects – he ended up as an actuary – and he was a gentleman,” recalls Jim Telfer, who recently chose Smith as his right winger in an all-time greatest Scotland XV.

“The captain has to reach out and be able to bring people together and Arthur was an ideal person to do that with the Lions. I used to go to dinners with him where he was often the main speaker and he was so positive, even when he was dying. He knew his time was limited but he used to joke about it. I thought it was so brave he could talk about it like that. He was a joy to be with.”

The unassuming Smith had led Scotland to a first win in Wales since the 1930s in 1962, and also scored two tries in a thumping 20-6 victory in Dublin during that year’s Five Nations Championship.

“He was a very good winger,” Telfer recalls. “He could run at top pace but then appeared to accelerate into another speed without over-exerting himself at all. He was really a sprinter, a silken runner who would swerve in towards his opposite number and then swerve out again without looking like he was getting any faster.”

Cowan had first played alongside Smith as an 18-year-old on the first ever Scotland tour of South Africa in 1960. “I thought the world of Arthur,” he said. “He was nearly 10 years older than me and one of my heroes. I was very fortunate to play with him.

“He was a super chap and very good to everybody on that Lions Tour, but he didn’t go about telling people what they had to do or what they couldn’t do. He was just the captain of the team, but a very quiet captain. He had a very hard job out in South Africa.”

The Lions lost their principal playmaker, the England stand-off Richard Sharp, to a broken jaw sustained in a tackle by Springboks wing Mannetjies Roux in a first defeat of the Tour against Northern Transvaal, a week before the first Test.

Sharp didn’t return until the latter part of the Tour, and only played in the final two Tests.

“We really missed Richard,” said Cowan. “He was the one who was going to be running with the ball at the South Africans, whereas Gordon Waddell [the Scot who replaced Sharp at fly-half in the Test team] was more of a kicker. I was hoping to play with Richard; I’d played with him with the Barbarians and he was a wonderful runner who looked after his backs whereas Gordon, as good as he was, just seemed to kick the ball all the time, which didn’t suit my style of rugby.”

If Waddell’s tactics didn’t always meet with the approval of his outside backs, off the field he enjoyed a life-changing encounter when he met his future wife, Mary Oppenheimer – the daughter of one of South Africa’s leading businessmen Harry Oppenheimer, whose empire included the world renowned De Beers diamond company.

Waddell would return to South Africa to marry Miss Oppenheimer and forge a successful business career in the country before entering politics and winning election to the South African parliament in 1974 for the Progressive Party, which opposed the ruling National Party’s policies of apartheid.

In 1962 he had helped the Lions secure a 3-3 draw in their first encounter with the Springboks, Welsh centre Ken Jones scoring a try in front of 73,000 fans at Johannesburg’s Ellis Park.

But a 3-0 defeat in the second Test in Durban – via a lone penalty from South Africa fly-half Keith Oxlee – put the tourists on the back foot, and they succumbed 8-3 in the third Test in Cape Town.

With another defeat went the series, but the match was not without significance. It proved to be the first of a record 17 Tests in the famous red jersey for a young Willie John McBride.

“Willie John was 22 on that Tour,” Cowan recalls. “The world was his oyster. He got into the Test team later in the series, like me. There were a lot of more experienced players than him, but he was good, even then.

“By the time he went on the ’74 Tour, he knew everything about rugby, and touring, and looking after people. He had all that experience behind him.”

With captain Smith picking up an injury that ruled him out of the final Test, Cowan was drafted onto the wing for what was his final game of rugby union, at Bloemfontein’s Free State Stadium.

“It was fantastic,” he said. “Nobody can ever take that away from me. I was up against Mannetjies Roux, who was a very good player.”

Cowan scored the second of the Lions’ three tries, with fellow Scot Campbell-Lamerton – who would go on to skipper the 1966 Lions – grabbing their opener. But in a match out of keeping with the rest of a tight series, the Springboks ran in six tries to run out 34-14 winners and take the series 3-0.

“We were fairly well beaten in that one,” Cowan added. “It was the end of the Tour basically. We had been away a long time. I was OK, I was just a 20-year-old, but there were a lot of players who were married and some of their wives had children while they were away. A lot of them were very keen to get home with a month still to go. They had been away from their wives and children far too long.”

If it was a relief for some to finally head home, for others the adventure remains seared on the memory, the experience of a lifetime.

“I could have stayed out there a while longer,” quips Rollo. “I would do it again every month if I had the chance.”